The other day, I was able to work with a young man that was visiting from out of town. He was 13. It was the first time I had ever seen him swing.

When I first work with a player, I do a lot of observing early on. I’ll watch him go through his routines. I’ll observe the consistency of his swings. As he swings, I’ll prod him with calculated questions. I want to know what he feels like when he’s at his best. At his worst. What does he see? What is he focused on? What’s important to him? What kind of feedback does he receive from his coaches? What is the ball doing when he’s on? Off?

After I watch him work on the tee, we’ll go to flips. I’ll watch 15-20 swings. I won’t say a word. I’ll observe ball flight, contact quality, and consistency. I’ll film every swing. After I get a feel for his swing on flips, we’ll go to batting practice. I’ll go through the same routine. As the difficulty level of the task increases, I want to see the impact it has on the swing. Does the swing remain stable, or does it break down? If it breaks down, where and when does it break down? What are the stressors? Where is the athlete receiving the most amount of feedback during this process?

When I watched this player on the tee and flips, I could tell he was a pretty good athlete. He was hitting the ball pretty consistently. His swing signature didn’t change drastically. It remained pretty stable. When we went to batting practice, however, this started to change.

Below is one of his better swings from flips:

Below is one of his swings from batting practice:

From a macro level, these two swings are very different. One has much more leverage, consistency, and coverage. The other has much less. A disconnect had been identified. Here’s where the coaching process really begins. Instead of just telling him what he needed to do, we had to start peeling back layers. We can’t just focus on what changed. We need to focus on why the change in environment (flips to batting practice) created a breakdown in his swing.

Before I said a word about his mechanics, I showed the kid the two videos. I told him first to simply observe. Did they look the same? Different? If they looked different, where do they look different? Is it a clean transfer of energy, or is there a break in the chain somewhere?

As he observed the two videos, he gave me some really good feedback. When he watched his video of batting practice, he talked about how he felt very indecisive. He was second guessing himself. Instead of feeling confident and aggressive, he felt like he was on the defense. This, as you could guess, has an impact on swing mechanics.

If we don’t feel comfortable in the box, we’re not going to be able to optimize our mechanical efficiency. This, as a result, is where we decided to start. The next round, I gave him a different mindset. I wanted him to be much more aggressive in the zone. I can handle bad decisions. We all make bad decisions. What I cannot handle, however, is indecision. We can learn from bad decisions. We can’t learn if we never make one in the first place.

This round was a big improvement. Below is one of his better swings:

While the swings were better, some were still a little off. Instead of getting consistent leverage against his front side, he would peel open into foot plant. This made it really difficult to square up middle away fastballs – a pitch he admitted he’s had difficulty with in the past. If he didn’t cap them, he simply took them. If it doesn’t appear like a pitch we can hit, we’re not going to pull the trigger (which is why we need to be cautious when viewing increased walk rates as positive).

Seeing he was struggling to find a consistent and stable landing position, I went to the Constraints Learning Approach (CLA). Constraints bring your words to life by creating an obstacle to action. This obstacle optimizes feedback loops for learning. If you violate the design of the constraint, you’re going to get immediate feedback on whether or not you succeeded. There’s no gray area. You either did it better or worse.

In this situation, I noticed how he would set up slightly closed in his stance. On his worse swings, this angle would wind up slightly open. To change this, I set a PVC pipe just behind his heels that mirrored the angle of his set up. If he decided to stride and leak open, he would get immediate feedback from the PVC pipe on stride direction.

This created his best round yet:

In his previous rounds, the outside pitch had looked un-hittable. This was because he was in a poor position to hit it. When the front foot leaks open and the pelvis opens prematurely, it becomes really difficult to hold angles over the plate. We lose leverage. As a result, anything further away from our barrel looks really far away. It wasn’t a vision problem that was causing him to take fastballs on the middle out portion of the plate. It was a swing problem that subsequently impacted how he was seeing the ball.

The PVC angle created a positive swing adaptation. This created more affordances for action.

Along with some pretty cool swing adaptations:

Hitting becomes a lot easier when more pitches appear “hit-able.”

…

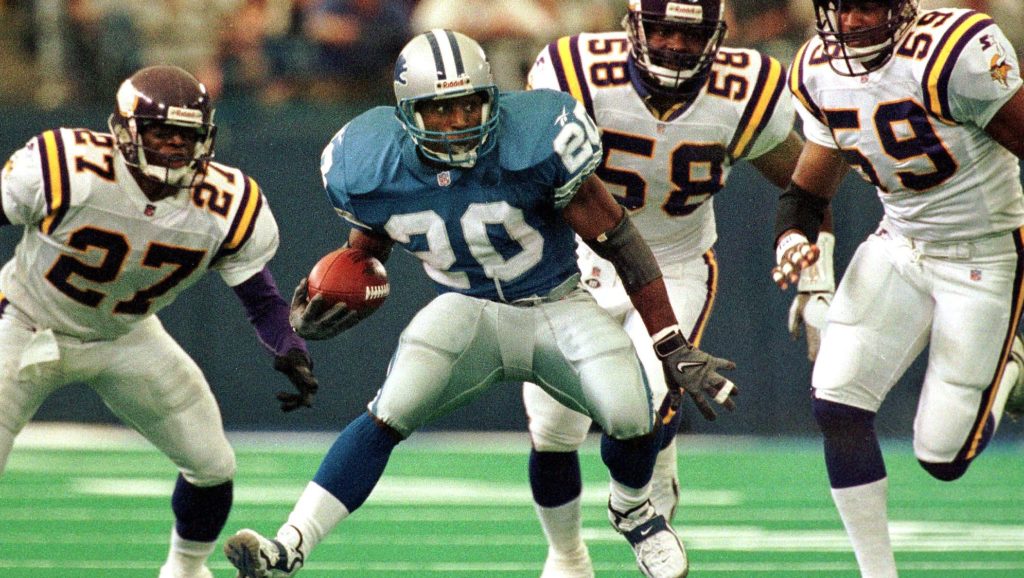

I’ve recently been going through Randy Sullivan’s book The SAVAGE Revolution. In his book, Sullivan talked about the concept of affordances. He explained it using an analogy. Him and Barry Sanders are looking at the same situation on a football field. The goal is to run through a hole created by the center and right guard. Sanders – given his speed, agility, and athleticism – is going to see that hole and dart through it without thinking. His physical ability creates more affordances for action. Randy, on the other hand, wouldn’t quite be able to hit the same hole. He does not possess the athleticism of Sanders, thus limiting his affordances for action.

They both saw the same hole, but they both saw it completely differently in terms of action potential. This wasn’t a vision problem. It was a problem of athleticism. If you don’t have a software solution that makes something seem achievable, you’re not going to attempt it.

This is what was happening above in our earlier rounds of batting practice. A lack of vision wasn’t the barrier to action. The swing was. Two hitters could be looking at the same exact set of pitches. If you have a better swing, you’re going to see the same pitches as much more “hit-able.” Just telling someone with a bad swing to swing at more pitches won’t influence better swing decisions. A better swing will.

If you’re working with an athlete who claims they can’t do something, don’t just chalk it up as a mental block. Try and figure out why they can’t do that. Is their current swing or delivery creating appropriate affordances for action? If it isn’t, where are the breakdowns? What’s the barrier to action? Is it a hardware problem, software solution, or a little bit of both?

Evaluate – and then coach – accordingly.