Everyone has that kid in their program.

Whenever he’s around, he’s not really working. He’s either goofing off, laughing, engaging in unproductive activities, or he’s a distraction to the training environment. As a coach, nothing is more frustrating when you have one of these players around. They’re tough to coach, relate to, and empathize with. It just doesn’t seem like they “get” it. Why don’t they get after it like everyone else? Why does it seem like they constantly need additional motivation? Instruction? Guidance?

If you were to describe a player like this, one – or several – of the traits below probably comes to mind:

- Lazy

- Unfocused

- No work ethic

- Distraction

- Talkative

- Comedian

- Uncoachable

Here’s the problem: We often think about traits as fixed behaviors. If we call someone stubborn, we’re viewing them as a stubborn person. We paint the trait as a part of their character. What we fail to realize is traits are not fixed. They’re context dependent. Stubborn people aren’t stubborn all the time. There are plenty of situations in which they’re very much the opposite of stubborn. They’re just stubborn in certain situations – which happen to be the ones you’ve observed. Traits don’t describe people. They describe behaviors from people in specific situations. Our “stubborn” athletes are no different.

Just think about it. Lazy athletes aren’t lazy all the time. Just watch them do something they’re really interested in (e.g. video games, backyard sports). They’re very motivated when they’re doing something they find genuine excitement in. They’re just lazy around you. We fall victim to the same trap. If you don’t like yard work, you’re not going to look or act really motivated when you cut the grass. You’re going to appear pretty lazy. It’s not that you’re a lazy person. You just act lazy when you do things you’re not that interested in. In this situation, it’s yard work.

Whats seems like a people problem is often a situation problem.

If you’re working with a difficult athlete, you can’t just view the athlete as a difficult person. They want to work. You just have to get them excited about work. It’s not a matter of discipline. Self control is in short supply. If you’re hungry and the first thing you see when you open your pantry is a plate of cookies, you’re not going to think twice. You’re going to eat the cookies. The problem isn’t the fact that you made the decision to eat the cookies. It’s the fact that the cookies were there in the first place. The best way to influence change isn’t by tweaking the person. It’s by tweaking the environment.

If the first thing you saw when you were hungry was a bowl of fruit, you would have made a much different – and better – decision. It’s not that you were “undisciplined.” You just fell victim to a poorly designed environment. This is how we need to handle our difficult athletes. We need to make it harder to find the cookies and easier to find the bowl of fruit.

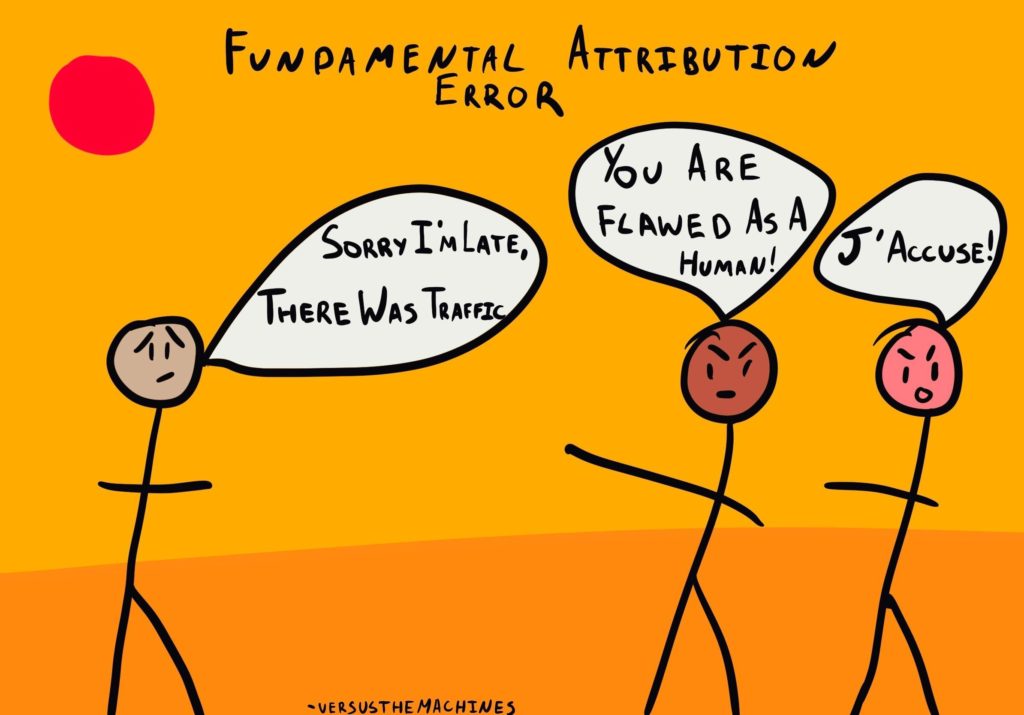

Our natural response to difficult athletes is a classic case of fundamental attribution error: It’s not our fault they’re lazy, constantly goofing off, and not getting results. It’s their fault. We’re quick to label and slow to investigate. If we instead focused on the situation in which they displayed these kinds of behaviors, we could be more proactive. We’re not just seeing the behaviors as character traits. We’re seeing them as a byproduct of a situation that unconsciously encourages them. Our antidote to difficult athletes isn’t a matter of self control. It’s environment design: How can we create a space that encourages good behaviors and discourages bad ones?

If you’re struggling to connect with one or more of your athletes, it’s time you start examining the environment in which you operate in. Below are some tips on how to make the most of yours:

- Make what’s desirable slightly easier

- When athletes come in the door, they’re hungry. They’re going to pick and choose from the food options that are most visible and accessible. If you lay out the healthy ones ahead of time, they’re going to become a much more popular option. From a training perspective, this includes tools, technology (there’s nothing more aggravating than spending 20 minutes setting up something you use for 10), equipment, or video. If your core velocity belt is a pain in the ass to get out and put back, kids aren’t going to use it. If it’s easier to set up for and capture video, kids are going to do it more. If trash cans are more visible throughout the facility, less trash will be left on the training floor. If you want to encourage something, clear the path. We’re naturally going to gravitate towards the road of least resistance.

- Make what’s undesirable slightly harder

- Dealing with kids that have bad habits? Make it harder to access those bad habits. Have them put their phones away and out of sight. Have them train with kids that posses strong training habits and work ethic. Give them space where they can work alone for a period of time. Hide the training tool they’re constantly playing around with. Move tables and chairs for leisure off of the training floor. The more they have to work to access what’s undesirable, the less likely they’re going to do what’s undesirable.

- Gamify it

- There’s nothing sexy about consistent training habits or daily routines. They’re pretty boring, to be honest. It doesn’t make them unimportant. It just makes them unappealing. An easy way to spice up what’s monotonous is to put something on the line. Play a game of pig off the tee. Host a line drive or exit velocity competition. Create a mini game situation and draft up teams. What started as batting practice has now become an adrenaline-fused competition. You didn’t really change the environment. You just added consequences for failure. This is often enough to break the monotony of daily training practices.

- Improve your feedback loops

- If you’re working with “unmotivated” or “unfocused” kids, there’s a chance they just don’t have anything to get motivated or focused about. It’s not that they have a short attention span. These are the same kids that play video games for three to four hours at a time without getting bored, unfocused, or uninterested. A big reason behind this comes down to feedback loops. When we play video games, we have clear, concise, and immediate feedback on whether we accomplished something or failed (yes, kids have the ability to wrestle with failure without getting deterred when presented in the right context). We have to create the same thing in our training environment. If they don’t know what they’re trying to accomplish (objective), how they can accomplish it (strategy), or have clear and immediate feedback on how well they were able to do it (velo, target, sound, video), it’s going to be tough to create any kind of motivation. My good friend Lantz Wheeler says it best: Making adjustments comes down to multi-sensory integration. We need to gather as much feedback as possible from as many different senses (sight, auditory, kinesthetic, etc.) as possible. Think about the environment you’re training kids in. Is your training space rich in sensory feedback, or is the only kind of feedback coming from your mouth and eyes?

- Make them a part of it

- Players want to be a part of their development process. The best way to get them involved is to invite them in. Giving some degree of autonomy can go a long way. It’s a lot easier to get excited about an exercise or drill variation you picked rather than one that someone else picked. They’re still accomplishing what you want them to do. They’re just doing it in a way that’s more enjoyable. You can also give them some leadership responsibilities. Have them lead the warm up or instruct a new athlete on how to execute a specific movement. When you give a difficult athlete some level of responsibility, they’re going to wear it like a badge of honor. This is a great way to make them your advocates – not adversaries.

- Visuals

- While this was covered in feedback loops, I felt it was important enough to cover it twice. Kids are exceptional visual learners, especially in today’s society. Most people are drowning in visual stimuli on a daily basis. Use this to your advantage. Capture the good moments as much as possible. Show kids video and visuals from some of the best players in the game. When you can show them what you’re looking for, you don’t have to verbalize it. The visuals bring the concepts to life. Words don’t always accomplish this. If you’re telling a kid to do something and they aren’t making it happen, consider the visual examples they’re working with. Do they know what they look like right now? Do they have a model for what it should look like? Are you consistently updating their mental model by showing them how they’re making – or not making – specific adjustments?

- Commend work habits, not personality traits

- If you’re working with a kid that appears stubborn, consider how comfortable they are with stretching their limits. If they’ve always been praised as the smart or athletic kid, everything they do is going to protect that identity. As a result, you have to be cautious with how you praise them. Don’t praise fixed personality traits. Praise work habits. If kids want to constantly look like the best, they’re not going to want to perform in situations where they don’t look the best. If you praise them for how hard they work, however, they’re going to work hard regardless of whether it looks good or not. This is better known as the fixed vs. growth mindset. How we talk to kids on a daily basis influences whether they think their abilities are malleable or not. What you see on the surface as “stubborn” might be linked to a fixed perception of their abilities. If you want to change their behavior, you have to start with their beliefs. Once they believe they no longer have to protect an identity someone else gave them, they can train and compete with a new sense of confidence. This is called a growth mindset.

We are all products of our environment. Don’t just look at the behavior. Investigate why that behavior is happening. It’s natural to fall into the trap of fundamental attribution error. Our antidote to this is context. What looks like a people problem is often a situation problem. Clear the path to what you want and bury the path that represents what you don’t.If our decision making is in short supply, we can’t afford to waste it making good decisions. Make people waste it on bad ones.

They won’t make those mistakes for long.