(originally posted 5/21/2021)

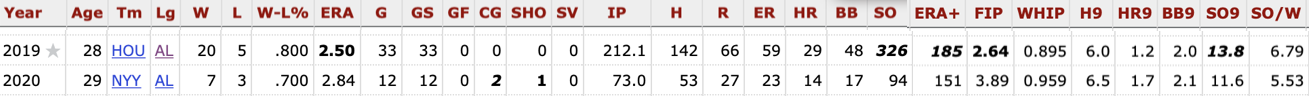

After a good – but not great – 2020 campaign, Gerrit Cole is on pace for the best season of his career in 2021.

Through eight starts, Cole has thrown 52.2 IP, struck out 78, and walked just three batters for absurd K/BB of 26.0. He’s allowed just eight earned runs and currently owns a 1.37 ERA, 0.684 WHIP, 1.11 FIP, and leads the MLB in WAR with 2.8. If it wasn’t for some guy named Jacob deGrom, he’d be pacing the league in all of those categories but one (ERA: Means 1.21).

While we can often become immune to success because of previous dominance (e.g. Mike Trout), there is nothing ordinary about Gerrit Cole’s second season in pinstripes. DeGrom might be stealing the show in 2021, but Cole’s numbers paint a pretty convincing story: He is not the same pitcher he was in 2020. He is much better, and the film backs it up.

Last year, we got a ton of traction talking about Gerrit Cole. We knew he wasn’t the same pitcher from 2019 after watching him throw just one pitch. It’s not to say he was bad, but we knew the changes he made weren’t good changes. Those predictions ended up aging pretty well.

This year is a different story. The film and the numbers give us a really good idea that Cole made some conscious and deliberate changes this past offseason to return to circa ’19 form. So far, those changes have paid huge dividends. If he keeps this pace up, he doesn’t just have a chance to match what he did two years ago. He has a chance to surpass it. If he does, he’ll be in a position to do something he’s never done before in his nine-year big league career: win a Cy Young.

To start this discussion, let’s go to the film room. Below is a pitch Cole threw in 2019 at 100 mph. It was his 110th pitch of the game.

When it comes to pitching and hitting, a good chunk of our success comes down to our ability to move a weight through space as efficiently as possible. We’re trying to impart the most amount of force using the least amount of energy to maximize our production. If we look at the video above, it’s no mistake Cole is throwing 100 mph late in games. He’s moving to and through positions of leverage that help him maximize his efficiency on the mound.

To give you a feel for this, below is where Cole gets to at foot strike (left) and how he compares to some of the hardest throwers in the game. Pay close attention to the lower half. What do you notice?

Notice how his pelvis stays closed into landing and resists opening up? See how anchored his back leg is and how his shoelaces face towards third base? This position is really important. When Cole’s front foot comes back down to earth, his trunk and pelvis are closed, centered, and connected. This puts him in a strong position of leverage when it’s time to stop and rotate. He’s not flying open, leaking energy, or losing connection to the ground. Everything is lined up so the can get his best punch off consistently and effectively.

As Cole starts to rotate and impart force into the ball, we start to see what made him really special: His braking system is elite. Cole doesn’t just produce a ton of force. He does it with ease. He stops and rotates on a dime. There’s no folding, yanking, or leaking energy into release. Everything becomes really stable really fast creating for a clean transfer of energy up the chain.

When you pair an elite engine with a strong set of brakes, you get this: Easy gas. The best don’t just produce a ton of force. They do it with ease.

Let’s go to 2020. Below is a 98 mph fastball from Cole during an outing against Tampa Bay. Take a close look at the positions and transfer of energy during this throw. Then compare it back to 2019.

Different, right?

Before we break it down, let’s go to Cole’s May 12 start against Tampa Bay where he threw eight scoreless innings. Below is his last pitch at 99 mph. Pay attention to the positions he gets to, the transfer of energy, and how it compares to 2020.

In 2020, Cole’s average fastball lost some zip dropping from 97.3 mph to 96.9 mph. This year it’s back up to 97.4 (from FanGraphs). These two videos give us a really good idea why. Last season, he wasn’t moving to and through the same positions he once was in ’19. As a result, his performance regressed.

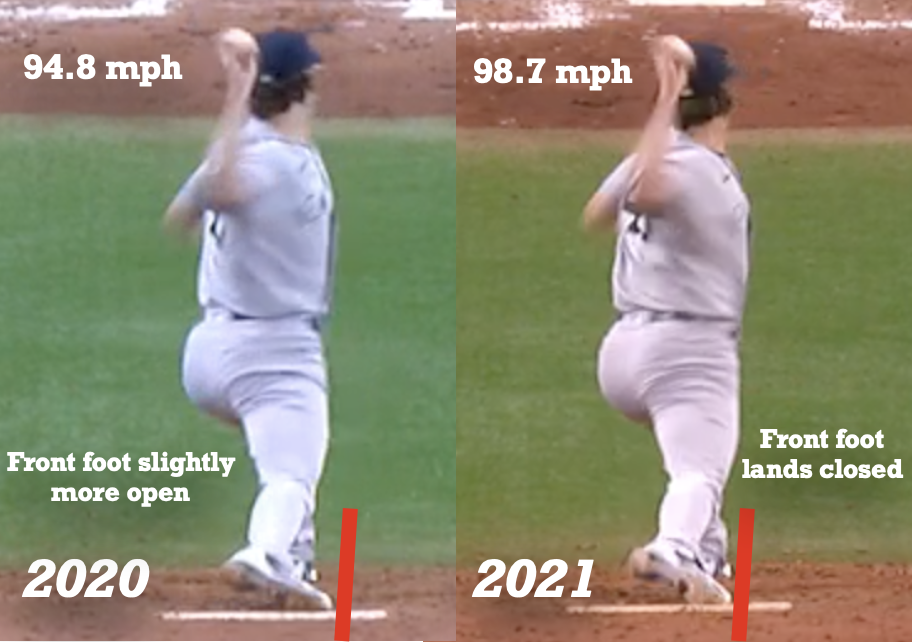

Below is a snapshot of both videos at foot plant. Take a look at the difference in his front foot.

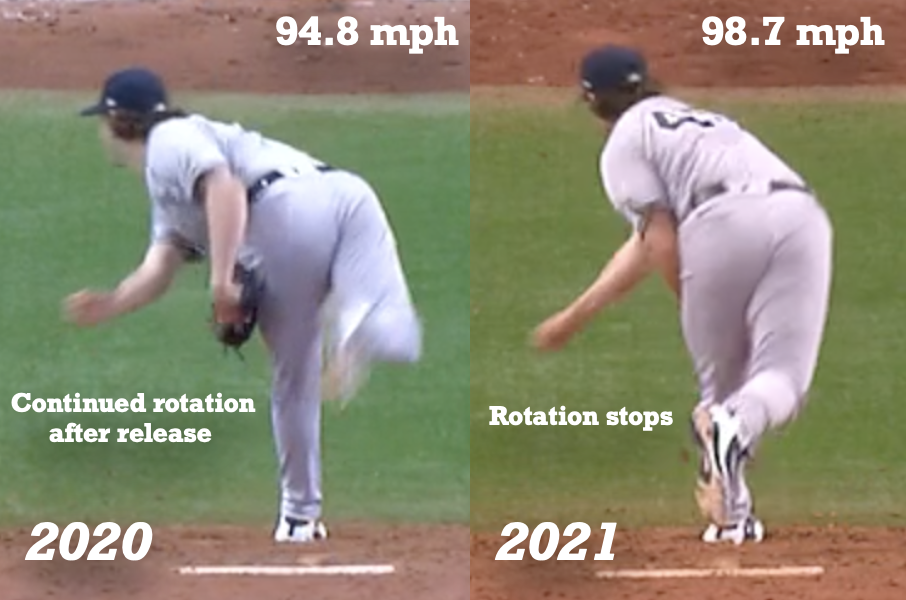

Notice how it’s slightly more open in 2020? Now let’s look at where he gets to after release.

Huge difference.

In 2020, Cole never got to a point of crossbody tension where he was able to stop and impart force into the ball. Everything continued to spin towards the first base dugout after release. His brakes weren’t working the way they used to. This caused him to lose velocity, miss high and arm side with his fastball, and yank breaking balls out of the zone. Below are his pitch distribution charts from 2019 vs. 2020 that show some of these differences. It was a small sample size in 2020, but the charts do show some key differences that illustrate what we would expect.

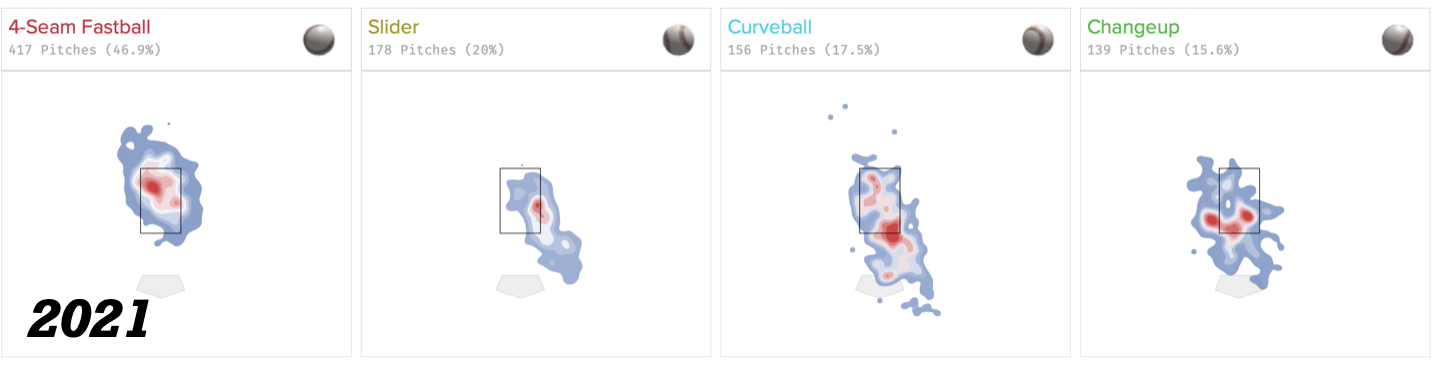

This season, he’s improved on that a ton. He’s landing a little more closed, he’s stopping a lot better, and more of his energy is getting transmitted into the baseball. He’s no longer losing a ton of energy towards the first base dugout. As a result, his velocity is back up and his command is the best it’s ever been in his career (0.78 BB/9). It’s still a little early to draw significant conclusions from his 2021 pitch distribution, but you can start to see some differences. He’s pounding the zone more with his breaking ball, he’s throwing more glove side fastballs (it’s tough to throw these when you’re constantly spinning), and he’s using his change up a lot more. Remember this part – it’s important for later.

I’m not quite sure why Cole made the adjustments that he did last year, but I do know this: His extension numbers changed drastically. Whether it was Cole, a coach, or someone from the front office, someone thought it would be a better idea going into 2020 if he released the ball closer to home plate. The problem with this is not all extension is created equal. Just telling someone to get more of it and actually creating it the right way are two completely different things.

In Cole’s situation, I have a theory trying to get more of it made him worse.

To break this down, let’s look at some data. In ’19, Cole had 6.3 feet of extension on his fastball, 5.9 feet on his slider, and 5.7 on his curveball. At first glance, these numbers seemed a little off. I wouldn’t expect a pitcher to have four to six inches of difference in extension between their fastball and breaking ball. As a result, I did some digging and gathered extension numbers for the 10 best sliders and curveballs, according to wSL/C and wCB/C from Fangraphs. I then compared these numbers to the extension they got on their fastballs. Below is what I found.

*all extension numbers from Baseball Savant

Fastball vs. Slider extension

- Yu Darvish: FB 6.4, SL 6.3 (+0.1)

- John Means: FB 6.1, SL 6.2 (-0.1)

- Zach Plesac – Both 6.2 (0)

- Joe Musgrove: FB 5.8, SL 5.9 (-0.1)

- Chris Bassit: FB 6.3, SL 6.4 (-0.1)

- Jacob deGrom: FB 7, SL 6.9 (+0.1)

- Shane Bieber: FB 6.6, SL 6.5 (+0.1)

- Nick Pivetta: FB 6.6, SL 6.4 (+0.2)

- DeSclafani: Both 6.6 (0)

- German Marquez: Both 5.4 (0)

Fastball vs. Curveball extension

- Lance McCullers: FB (sinker) 6.2, CB 6.0 (+0.2)

- Brandon Woodruff: FB 6.6, CB 6.5 (+0.1

- Kyle Gibson: FB 6.7, CB 6.6 (+0.1)

- Yu Darvish: Both 6.4 (0)

- Jordan Montgomery: FB 6.7, CB 6.6 (+0.1)

- Julio Urias: FB 5.6, CB 5.5 (+0.1)

- Zach Plesac: FB 6.2, CB 6.1 (+0.1)

- Tyler Glasnow: FB 7.4, CB 7.2 (+0.2)

- Jake Arrieta: FB (sinker): 5.9, CB 5.8 (+0.1)

- Wade Miley: FB: 6.2, CB 6.1 (+0.1)

As it turns out, I was right. Having 4 inches of extension difference between a fastball/slider and 6 between a fastball/curveball isn’t just big. It’s astronomical. But it doesn’t mean it’s bad. Given the context of Cole’s historic season, I wouldn’t view the extension differences as a red flag. It’s very unique, but it didn’t seem to be a problem for him. His pitches still managed to tunnel very well off of each other.

Here’s where it gets interesting. In 2020, Cole added 3 inches of extension to his fastball, 5 inches to his slider, and 7 (yes, 7 inches) to his curveball. As a result, the gap in extension between his fastball and both pitches dropped to two inches (FB: 6’6″, CB/SL: 6’4″). This kind of a change isn’t an accident. These numbers were indication of a conscious and deliberate decision.

It didn’t have a positive influence on both pitches, either. His curveball lost 6.6 inches of horizontal movement, 4.8 inches of vertical movement, and 80 rpm of spin. His slider only gained 0.2 inches of horizontal movement, but lost 0.8 inches of vertical movement and 42 rpm of spin. Both performed relatively similar in terms of wOBA, but underperformed in ’20 against xwOBA (SL wOBA: 0.222, xwOBA .205, CB wOBA: .252, wxOBA .218). Of all his pitches, Cole’s fastball took the biggest hit. In ‘19, hitters batted .166, slugged .384, and totalled a .254 wOBA against four seamers. Last season, those numbers jumped to .226, .466, and .315, respectively.

Adding extension is often a slippery slope for most pitchers. It’s one thing to know it happens. It’s another to actually make it happen in a beneficial and impactful way. For Cole, there’s a chance that focusing on releasing the ball closer to home could explain why he was moving different last season. He was forcing himself to create more extension by actively reaching his hand out and trying to rotate more towards home. This is where the spinning and peeling open into release could have started. He was trying to achieve something that might have been important, but he wasn’t doing it in a way that reinforced good sequencing and decelerating patterns. He wasn’t stopping and whipping his arm through to create extension. He was dragging his arm through to artificially create extension. There’s a huge difference between these two.

While we won’t know the real reasons without insider info, I have a feeling this is something that was addressed with Cole going into the 2020 season. It might have been a problem, but the solution they came up with didn’t help address the problem. They only magnified it – if there was a problem in the first place.

Another issue Cole ran into in 2020 was getting left-handed hitters out. Last season, Cole’s ERA against right handers was 2.09. Against lefties, it was 3.90 – his worst mark since 2017. While Cole’s made his money off high spin heaters and breaking balls, he’s started to rely on his change up a lot more this season. He’s used 70.7% of them against left handers and is throwing the pitch at a career-high 15.5% clip. Last season, he relied on the pitch just 5.6% of the time. So far, it’s been really, really good. Hitters are batting just .053 against change ups, slugging .079, and have accumulated a .057 wOBA. Only four lefties have gotten hits off of it. He no longer has a gap in ERA between left and right handed hitters. Both have accumulated a 1.37 ERA against him through eight starts this season.

Out of his 78 strikeout victims this season, 42 have been left handed. Seven of his punch outs have come on curveballs. Sixteen – more than double – have come courtesy of the change up:

Cole’s always had a pretty good change up (41.2% whiff rate in 2019), but now he’s finally trusting it and throwing it at a significant clip. As a result, he’s developed a weapon that he can use to put lefties away deep into accounts. He’s throwing his four seamer and slider less as a result (4 seam -6.2%, SL – 4.1%), but both have been more effective. Going into this season, we all knew Cole had three elite weapons. Now he has four. If you’re a hitter, that’s a problem. Cole has yet again reinvented himself on the mound. He’s moving better, he’s more unpredictable than he’s ever been, and he’s currently on the first track to win his first ever Cy Young award.

Whether he does or not, what he’s done so far this season has been pretty special. It’s going to be even more fun to watch him the rest of the way.