(originally posted 8/30/20)

The other day I sat down and went back through some baseball from earlier in the day that featured a doubleheader between the Mariners and Padres. I was particularly interested in this series because Manny Machado – one of the anchors on my fantasy team – had left the yard on three different occasions between both games. Knowing I missed out on this, I decided to go back and watch game two so I could catch Machado’s third blast of the day and get some cool angles from one of the hottest hitters in baseball.

What I didn’t expect was that I’d stumble on to one of baseball’s hidden games so far in 2020.

In the second half of the doubleheader, the Padres sent out ex-Angels pitcher Garrett Richards to square off against Yusei Kikuchi – the second year left hander out of Japan who joined Seattle last year after eight seasons in the Nippon Professional Baseball league. If you were a Padres fan, you probably didn’t watch much of the game after what happened early on. Richards failed to get out of the first, surrendered six, and left with San Diego facing a 6-0 deficit before they even had a chance to touch a bat. It never really got much closer from here.

Part of the reason is because the Kikuchi the Padres saw this year was a lot different than the guy they saw last year.

Now I didn’t really care to watch Kikuchi – or the rest of the game considering the top half of the first – but I was really interested in checking out Machado’s third homer of the day. It just so happened the hitter that bats before him in the lineup is a guy named Fernando Tatis Jr. – arguably baseball’s most electric hitter in 2020. When someone like Tatis steps into the box, you just stop what you’re doing and watch. You never really know what kind of a show he’s about to put on.

However, the must watch entertainment didn’t come from the box during that at-bat. It came from 60 feet six inches away. Kikuchi made quick work of the standout Padres shortstop sending Tatis back to the dugout in just four pitches. They looked like this:

- SL: 82.4 mph, K (foul ball)

- FF: 97.6 mph, ball

- FF: 96.8 mph, K (foul ball)

- CH: 89.8 mph, K (swinging)

Let me tell you, I’ve never pulled up Baseball Savant quicker before in my life.

After glancing through some numbers and making sure my eyes weren’t playing a trick on me, I figured out what the Padres unfortunately figured out that evening: This was not the same guy that sputtered to a 6-11 record in ’19 and accumulated a disappointing 5.46 ERA in 161.2 IP.

This Kikuchi was different, and he sure had my attention.

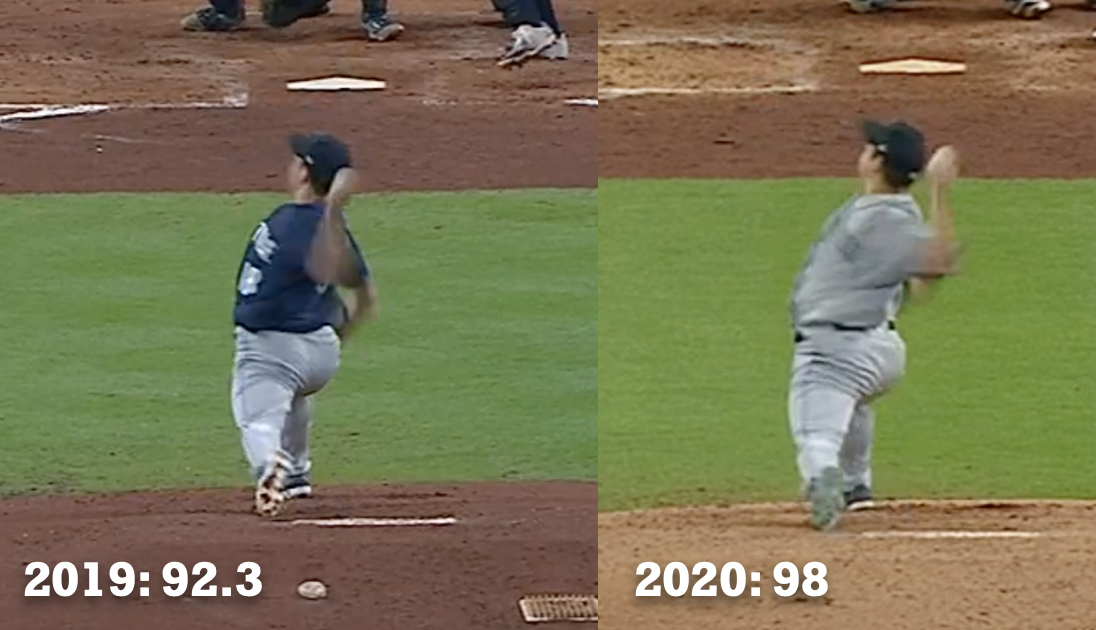

The Japanese native had been known to run it up into the mid 90s during his time in the Nipppon Professional Baseball league, but we didn’t really see 97.6 or 96.8 last year. In his first year in a big league uniform, Kikuchi’s four seam fastball averaged just 92.5 mph – a tick below the league average of 93.4. Hitters slugged .622 on it, accumulated a .410 wOBA against it, and whiffed at it just 19% of the time. In other words, it just wasn’t a really good pitch.

Now let’s look at the data so far from 2020. Through five starts, Kikuchi’s four seamer is averaging a blistering 95.2 mph – up 2.7 mph from his average heater in ‘19. As you could probably guess, it’s performed better in games as hitters are slugging .438 and have accumulated a wOBA of .357 against it – both improvements from ’19. It’s also getting whiffs at a career-high 26.4% of the time – a 10.4% increase from last year. If that doesn’t impress you, I think it’s worth noting that so far this season Gerrit Cole – the guy who set a MLB record for K/9 last season – is getting whiffs on his fastball just 25.7% of the time.

Let that sink in for a second: Yusei Kikuchi is missing more bats this year with his heater than Gerrit Cole.

Considering the left hander’s disappointing first season in the states, the increased fastball velocity and improved game performance is an encouraging sign that there’s a lot more in the tank than what we originally thought. However, here’s the funny part: Kikuchi is using his new and improved heater less this season.

In 2019, Kikuchi threw his four seamer roughly half the time at a 49% clip. This year, he’s throwing it just 39.9% of the time. Throwing heaters less is something that’s become a trend across Major League Baseball considering what teams know about how hitters perform against pitches that aren’t straight. However, the whole goal is to throw pitches that perform the best most often. If Kikuchi’s heater is performing much better this season, why wouldn’t he subsequently be using it more?

Well, a big reason why he hasn’t is because he’s started throwing something that’s performed even better: His new cut fastball.

Through five starts, Kikuchi’s new cutter has become his primary weapon throwing it at a 41.5% clip. It’s averaging 92.3 mph (just 0.3 mph slower than his four seamer from last year lol), generating whiffs 32.9% of the time, hitters are slugging just .283, and have accumulated a .277 wOBA against it. Kikuchi’s fastball has been good, but his new cutter has been really good. Just check out how is measures up against three of the best cutters in the game from Kenley Jansen, Aaron Civale, and Yu Darvish:

- Jansen: 91.2 mph, SLG .207, wOBA .180, 26.9% Whiff%

- Civale: 87.1 mph, SLG .459, wOBA .291, 30.9 Whiff%

- Darvish: 87.1 mph, SLG .359, wOBA .273, 36.8 Whiff%

Not bad at all for a pitch he didn’t throw last year. So let’s start to make sense of some of this data. How did Kikuchi go from a pitcher who struggled to touch 96 last year and evolve into someone who’s getting more fastball whiffs than Gerrit Cole currently is? To figure this one out, let’s take a closer look at the film. New data isn’t just created out of thin air – it’s created by new movement patterns.

“I consider saying “balance,” but instead I mumble something about making more natural motions. Latta says he doesn’t want me to reduce what we did to a number; better numbers are the by-products of better body movement.” – from The MVP Machine by Ben Lindbergh & Travis Sawchik

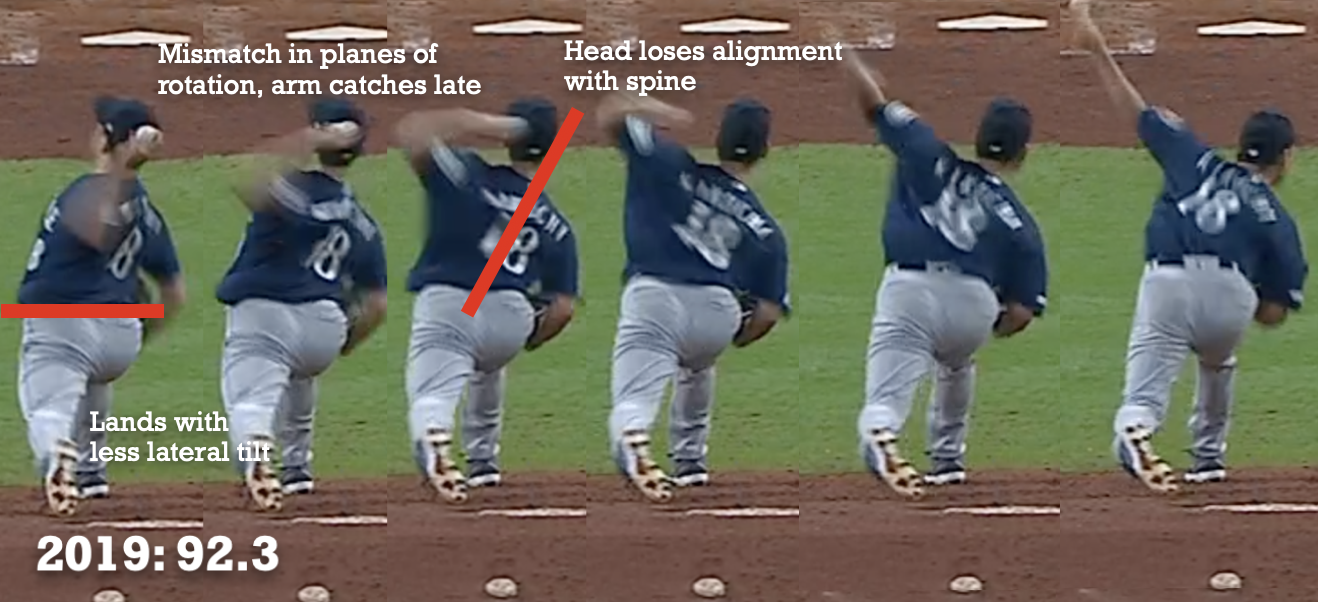

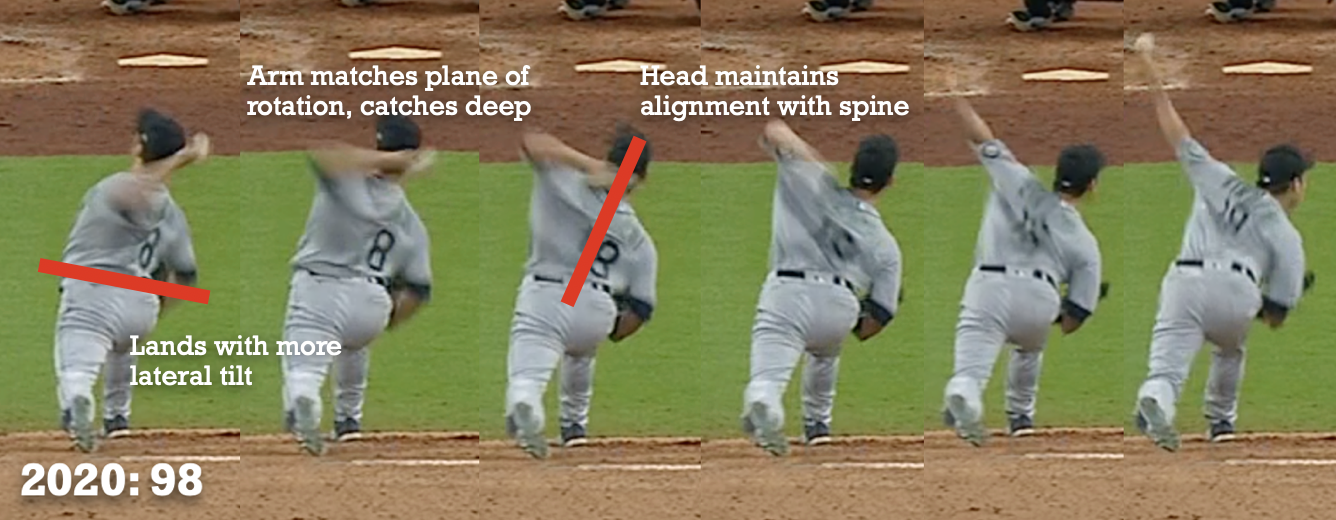

If we look at the film of Kikuchi from this season, it’s no mistake he’s blowing cheese and missing bats – his movement patterns have gotten way better. He’s getting to better positions, moving more efficiently through them, and it’s giving him the ability to do things like throw 98 and decelerate like an absolute menace:

Now the decel was there last year – don’t get me wrong – but the velocity wasn’t and the decel wasn’t showing up nearly as much as it is this year. This is directly related to the positions he was getting to and moving through from a year ago.

A couple of years ago, 108 Performance ran a study where they tested a group of arms from their facility to see what kind of an impact teaching the arm recoil would have on their delivery. Out of all the guys tested, they found the pitches thrown with the arm recoil produced the greatest amount of average ground reaction forces on the front leg, back leg, total power, and total ground reaction forces. They also produced better sequences, created more effective hip to shoulder separation, increased ball velocities, and on top of this elbow valgus stress decreased by an average of 37 percent. These findings challenged conventional theory in baseball which claimed the recoil was a detriment to performance and made guys more susceptible to injury. Turns out, the study actually proved the opposite: Pitchers were able to maximize the amount of force they produced while subsequently placing less stress on the elbow.

So let’s think about why this would happen. The reason why the arm recoils or gets peeled back after the throw is because it has no other choice – there is so much tension present in the system at that point in time from the upper half and lower half working reciprocally against one another. In other words, the rubber band has been stretched as far as it can go in either direction. As a result, the arm has no where else to go and is peeled back due to a golgi tendon reflex – the same exact reflex that causes your leg to kick out when doctors tap your knee. Dr. Ferree talked about this in their 2018 Palooza presentation saying how this reflex is actually a built in protective mechanism your body uses to prevent muscles from becoming overstretched which would make them more susceptible to tears and other similar injuries. In Eugene’s words: “It’s the ultimate sign of decelerator strength and efficiency with direction.”

Just remember this: Don’t get married to the recoil by itself – get married to things that need to happen so the recoil canhappen.

Kikuchi isn’t pimping the finish this year for the hell of it – he’s doing it because he’s getting into stronger positions which allow him to slam on the brakes and transfer energy up the chain more quickly and efficiently.

If we dive into these positions, we notice right off the bat that Kikuchi is able to stay closed longer into landing which prevents his pelvis from opening up too soon and getting in the way. This gives him the ability to line everything up down low so it can grab and stabilize when he needs it to (front foot strike). The quicker things stabilize down low, the quicker the pelvis can stop and slingshot the torso around it so energy can get transferred up the chain. This is where the decel is coming from – Kikuchi is bracing and stopping so well which creates an insane amount of tension that has no where to go after ball release. He’s able to pull this off because he’s doing a much better job closing off into landing:

Notice the position of Kikuchi’s arm on the right, the wrinkles in his rear glute, the direction of his stride, and the amount jersey and belt buckle we can see from behind. This tells us that Kikuchi is staying closed much longer which keeps his torso connected to his pelvis and gives his arm the space and freedom it needs to get up on time, catch the trunk earlier, and throw his punch from deeper:

Kikuchi’s uptick in velocity is no mistake – guys who catch the trunk early and decel like beasts tend to throw fuzz.

While this explains a ton about the increased velocity, Kikuchi has also made an interesting adjustment to his delivery when there’s no pressure to control the running game (he goes out of the stretch all the time). He ends up picking his leg up a little higher and actually takes his back heel out of the ground when he gets to peak leg lift:

This mechanism is pretty interesting and I have to imagine it was a conscious change by either Kikuchi or one of his coaches. Either way, as weird as it might seem, I think it could have helped him start to get a better feel for the positions we talked about above. We see a lot of big league arms who “release” their back foot and let it slip into more of an externally rotated position as they get into leg lift. This creates a more advantageous position for guys who don’t have a lot of internal rotation in their back hip as they move down the mound:

We also see it from hitters too:

In Kikuchi’s case, he’s creating a similar mechanism where he’s releasing his back foot and getting rid of early tension that can put the pelvis in a compromised position where it gets stuck and has to push out of the ground. Eugene likes to think about this move as a “release” of the back foot followed by a “float” of the pelvis which then creates a “late anchor.” We know the feet need to grab and anchor into the ground at foot strike so the pelvis can stabilize, but we also don’t want that anchor to happen too soon. We want to anchor in when it’s time to throw our punch – not well before it when we’re not ready. If the anchor happens too early, we get put into a position where we can’t hold on to tension any longer and the sequence falls apart. This is why the release is so important in the beginning – by letting go of tension early, we’re able to create tension later when it matters.

From here, the pelvis is able to float down the mound and bring the extremities along for the ride. The legs and arms shouldn’t work independently from the middle – they should be slaves to it. The more proximal we can get, the more efficient things tend to become. This creates the late anchor – we’re able to grab on to the ground and create tension when we need it because we are proximally to distally in the best position possible to throw our punch. As a result, Kikuchi is able to stay closed longer, use his backside better, and optimize his ability to put force into the ground. If you want to get force out of the ground, you have to learn how to put some into it.

As for what created all of this, it’s tough to tell from the outside. It could have been as simple as trying to pimp the finish as hard as he could or he might have had a big time unlock using the back heel release. One day he could have just showed up to the field, felt like a million bucks, and started popping out 98s. Who knows. However, it doesn’t really matter what happened because whatever he did is working and he looks really, really good.

So now for the most interesting part: Why aren’t people talking about Kikuchi this season?

The changes we just went over aren’t small changes – they have career-changing implications. Adding 1 mph to your average fastball is a big deal, let along 2.7 mph. Kikuchi’s getting into much better positions more consistently, he’s added a new weapon that’s become his primary pitch, and he’s striking out hitters at a career-high rate. Considering what we know and the strides Kikuchi has made so far in 2020, why aren’t more people talking about him?

That’s the thing: On the outside, it doesn’t look like Kikuchi has improved much at all. In five starts this season, the Japanese native is 1-2 and owns a whopping 6.12 ERA – even worse than the 5.46 he churned out a year ago.

When I first found out Kikuchi’s ERA stood at north of 6.0, I had already seen the film, looked into his pitch metrics, and saw the improvements he had made from a year ago. To say I was shocked would be an understatement. Everything I had looked up to that point suggested that Kikuchi should be doing a much better job of keeping runs off the scoreboard this season. Instead, he was actually doing worse.

Now I understand that his walk rate is higher this season (3.6 BB/9 vs. 2.8 BB/9 in ’19), but that’s just about the only thing that hasn’t improved besides ERA. He’s done a much better job keeping the ball in the yard (0.4 HR/9 vs. 2.0 HR/9 in ’19), he’s surrendering less base hits (9.0 H/9 vs. 10.9 H/9 in ’19), and his xSLUG (.357) and barrel % (2.9%) both rank top 7 percent among all pitchers. The film and data sure tell us Kikuchi has been a much better pitcher this season, but his 6.12 ERA seems to be telling us otherwise.

So now the question becomes this: How sure can we be that Kikuchi is having a better season when his ERA seems to be telling us otherwise? Better yet – how much value should we be putting into ERA in the first place?

Turns out, probably not a whole lot.

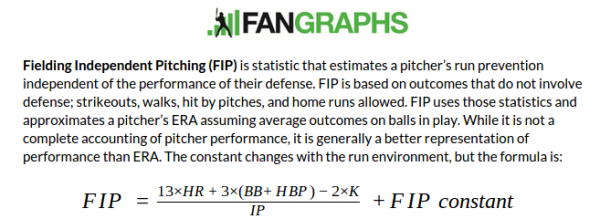

Fielding Independent Pitching (FIP), according to Fan Graphs, is a statistic that measures how well a pitcher is able to prevent runs by eliminating all batted ball outcomes that are influenced by defensive play. The only outcomes that are taken into account for the stat are ones that pitchers have complete control over: Strikeouts, walks, hit batsmen, and home runs. Below is the formula for it and an explanation behind it from Fan Graphs:

The idea behind measuring FIP is it gives us a better way to evaluate pitchers by stripping the influence of defense, luck, and sequencing. By focusing only on the outcomes pitchers can complete control over, FIP gives us a more stable metric that is not negatively influenced by things like bloop hits, shift beaters, and marginal defensive play. In other words, it gives us a better representation of a pitcher’s value because it only takes into account the outcomes pitchers are completely responsible for.

It also just might give us a better indication of the kind of season that Yusei Kikuchi is currently having.

As covered above, we know Kikuchi’s ERA so far this season is an abysmal 6.12 which ranks outside the top 50 pitchers in the MLB. His FIP, however, is only 2.71 which is good for 14th in all of Major League Baseball (minimum 20 IP). Just last season, Kikuchi sported a FIP of 5.71 – much closer to his ERA of 5.46. While Kikuchi over performed last season by 0.25 runs relative to his FIP, this year he’s underperforming by a league-high 3.48 runs. People might get turned off looking at the 6.12 ERA, but if they looked at his 2.71 FIP – and saw the 3 point improvement from last season – they might start to see what we’ve been explaining throughout the course of this article: Kikuchi is a much better pitcher this year and the data does validate it.

His 6.12 ERA is not a great indicator for the kind of pitcher he’s been.

In fact, you could argue Kikuchi has been one of the best pitchers in baseball so far this year. Before you write this statement off, let’s check out some of the guys he ranks ahead of in terms of FIP across the league (minimum 20 IP, statistics updated as of August 28):

- Trevor Bauer (15th – 2.76 FIP)

- Lance Lynn (30th – 3.37 FIP)

- Clayton Kershaw (34th – 3.46 FIP)

It just so happens that all three of these pitchers rank top 10 in ERA in the MLB:

- Bauer – 1.65 ERA (5th)

- Lynn – 1.59 ERA (4th)

- Kershaw – 1.80 ERA (9th)

Isn’t that pretty interesting. We’d all agree that Bauer, Lynn, and Kershaw are having pretty good seasons considering they’re sporting an ERA south of 2, but we also know that Kikuchi is outperforming all three in a statistic which we’ve just explained is a better representation of a pitcher’s true value. Kikuchi might not be on the pace of Shane Bieber or Jacob deGrom, but he has been performing at the level of a top 20 pitcher this season and it’s time we start giving him credit for it. Writing him off as a bad pitcher because of his 6.12 ERA just doesn’t make sense because we’re evaluating him based off a statistic he has very little control over in the first place.

If you wouldn’t want to be evaluated at your job based on things you had no influence over, why should we evaluate pitchers the same way?

We’ve come to the assumption that ERA is an accurate representation of a pitcher’s performance because we take out unearned runs, but there are plenty of “earned” runs that come across which really shouldn’t be credited to the pitcher. If you don’t believe me, just check out this inside the park “homerun” that Christian Yelich hit earlier this August.

🚨 INSIDE-THE-PARK HR FROM YELI 🚨 pic.twitter.com/zTwoL90nvS

— MLB (@MLB) August 7, 2020

Imagine being responsible for a four-way trip around the bases because your left fielder took a tumble into the netting after misjudging a can of corn. I understand that this situation would also impact a pitcher’s FIP because it’s technically a homer, but this is just one example of how defenses can impact games without it necessarily showing up in the scorebooks.

On top of this, there are plenty of subtle ways defenses can negatively impact run prevention that aren’t as glaring as this and unintentionally inflate ERA. Poor routes, bad positioning, slow transfers, average to below average defenders, and mental errors can all cost pitchers key “earned” runs which makes it seem as if they’re performing a lot worse than what they really are. ERA may take out all the runs that reach base via error, but it doesn’t account for a plethora of outcomes that pitchers have no control over. As a result, ERA provides an incomplete understanding of a pitcher’s true value because there are too many variables that lie outside the pitcher’s locus of control that can create a false illusion of how they’re really performing.

“If our goal is to determine how well a pitcher prevents runs, you want to compare them to each other in a manner that strips out all of the factors that lead to run scoring that have nothing to do with them. You want to know how well Kershaw and Lester would perform if they had the same defenders behind them. And you’d like it if their luck was even too.” – Neil Weinberg, from Fan Graphs article

It’s tough to pinpoint exactly why Kikuchi has underperformed at such a steep rate in reference to his FIP, but it’s never really one thing in the first place. It’s likely a bunch of different things that seemed insignificant in the moment that ended up accumulating into bigger things over time. Without meticulously looking into every single batted ball outcome off Kikuchi this season, we just have to understand that there are instances where luck favors some and works against others. It all evens out over time, but so far this season it’s not unreasonable to say that Kikuchi’s 6.12 ERA is probably an indication that he’s gotten a little unlucky at some critical moments throughout his first five starts.

After all, Kikuchi has only logged 25 innings so far this season. If you were to shave just one earned run off each of his five starts, his ERA would drop nearly two points to a more respectable 4.32. That one run could be a bloop hit with the infield in, a backside ground ball that beats a shift, a “swunt” that keeps a two out rally going, or a bad route in the outfield that gets chalked up as a hit.

So before you completely throw ERA out the window, I think it’s important to understand ERA is not a horrible stat that anti-correlates to success. Instead, it’s just an incomplete stat. Earned run average can give you valuable information just the way it has so far for us, but it can also be misleading if we don’t understand the context behind it. Just like anything, it’s not wise to put all of your eggs into one basket. If you’re solely evaluating pitchers based on their win-loss record and ERA, there’s a good chance you might be undervaluing someone inside your organization or missing on someone outside your organization. That’s a problem.

Yusei Kikuchi might have an ugly looking ERA right now, but it’s not an accurate representation of the kind of season that he’s had so far. If he continues at this pace, his luck will even out over time and his ERA will start to fall – but are we really that concerned with his ERA in the first place? If we want to normalize things across the board and evaluate pitchers based on what we know gives us the best representation of their value, it’s time to throw away ERA and start using FIP. Kikuchi is a great example of what we can miss if we value a player based on their ERA and fail to take into account their FIP.

It’s also time we start giving credit to Kikuchi. There is no reason we shouldn’t be talking about his transformation and the changes he’s made which are paying off for him in a big way. Coming off a disappointing first season, Kikuchi doubled down on his development and has turned himself into someone that will help the Mariners win games and hopefully compete for championships. His movement patterns are sound, the stuff is there, and the upside is tremendous for a young man who’s only in the middle of year two going toe to toe with the best hitters in the world.

You’re not going to want to miss what he does the rest of this season.